WHERE THERE’S SMOKE

THE POLITICS OF CLIMATE CHANGE ARE PLAYING OUT IN THE FIRE ON SADDLEWORTH MOOR.

The fires raging on moorland outside Manchester have fallen off the front pages of the national press. But they tell a vital story of climate change, land management, and our broken economic system.

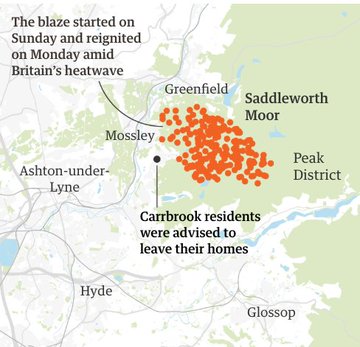

The huge wildfire that began on the 24th June on Saddleworth Moor has been declared a major incident, with over 30 homes evacuated and four schools closed in the area. Five days after the fire began, two other fires started to the north of Manchester before merging into one. The army has been called in, and firefighters are reportedly working 17 hour daysto try and control the blaze.

The latest report from the Greater Manchester Police is that the cause of the Saddleworth Moor fire is being treated as arson. But it was the heatwave conditions which enabled the fire to spread so rapidly across 2000 acres of moorland. With no rain forecast in the area for days, this is unlikely to change soon. And when it does rain, it’s possible that the extremely dry conditions will have compromised the moor’s ability to absorb rainfall, leading to flooding. Multiple scientists have warned that wildfires like these will become more frequent and severe as the changing climate creates more heatwaves.

And the origins of the changing climate are themselves locked away in the geography of the moor.

Saddleworth Moor is an area of peatland. Peat moors are the largest natural land store for carbon in the UK. When the peat is burned, it creates a positive feedback loop: it releases its carbon into the atmosphere as CO2; and in turn, degraded burned peatlands are less effective as a carbon sink. Climate change is both a cause and effect of the scale of the moorland fires.

But CO2 isn’t the only pollutant that peatlands absorb. As “the first industrial city”, 19thcentury Manchester was home to over 100 cotton mills and a rapidly expanding population. The surrounding moors will have soaked up “the fallout from many years of heavy industry”, according to Prof Susan Page of the University of Leicester. And the moorland fire may be releasing these toxic pollutants, absorbed during Manchester’s time as a hub of the Industrial Revolution, back into the air. There’s a grim poetry to the pollutants generated by the Industrial Revolution’s fossil fuel technologies being released through fire exacerbated by an extreme weather event.

But CO2 isn’t the only pollutant that peatlands absorb. As “the first industrial city”, 19thcentury Manchester was home to over 100 cotton mills and a rapidly expanding population. The surrounding moors will have soaked up “the fallout from many years of heavy industry”, according to Prof Susan Page of the University of Leicester. And the moorland fire may be releasing these toxic pollutants, absorbed during Manchester’s time as a hub of the Industrial Revolution, back into the air. There’s a grim poetry to the pollutants generated by the Industrial Revolution’s fossil fuel technologies being released through fire exacerbated by an extreme weather event.

In addition, the first moor fire spread across land which appears to be intensively managed for grouse shooting. This involves draining boggy ground and burning areas to encourage the growth of new heather. A representative from the RSPB said that grouse land management turns “wetlands with a high water table to a drier, heather-dominated environment”, making them less able to absorb water and more susceptible to wildfires. Land campaigner and co-creator of Who Owns England Guy Shrubsole has suggested that this may have been a contributing factor to the rapid spread of the fire.

According to Who Owns England, grouse moors “cover an area of England the size of Greater London, and rake in millions in public farm subsidies”. Our broken economic system is pumping public money towards land that is not being managed in the public interest — in fact, it is being managed in a way which is likely to expose the public to the dangers of wildfires, CO2 release, and flooding.

The Committee on Climate Change has also identified the burning of the peatland carbon sink as a barrier to fighting climate change, and recommend “the widespread restoration of upland peat habitats which includes a programme for reviewing existing consents for burning on protected sites”.

We have a tendency to see all these factors as separate, as if they do not interact with one another. But these aren’t stories that exist in isolation: the industrial pollutants stored in Greater Manchester’s peatlands are part of the same story as the management of huge swathes of English land for grouse shooting, and of the heatwave currently sweeping the country. Unfortunately these entangled connections with serious ramifications for the climate are often forgotten as MPs approve the expansion to Heathrow airport, and the government scraps plans for a tidal energy project in Swansea Bay.

The dynamics of climate change are more than the heat charts and emissions graphs we’ve become so familiar with. There are layers of interconnected geological, historical, and political forces at work — and a holistic response to climate change can only come from paying attention to them.

These dynamics of climate change, of extreme weather events, the Industrial Revolution, positive feedback loops, and a broken economic system, are playing out right now, on Saddleworth Moor.

Banner image: Flickr, Manchester fire, cropped

Where there’s smoke | New Economics Foundation

.

.

.

No comments:

Post a Comment