BBC Radio 4 - The Briefing Room, Why Did People Vote Leave?

It was about those Not in Employment, Education or Training:

Futures Forum: Brexit: and providing good quality jobs

It was about communities:

Futures Forum: Brexit: and looking beyond revolt: "If we’ve learned one thing in the last week, it is that communities – not Westminster - must agree what works for them."

And it was about 'elites':

Futures Forum: Brexit: and democracy: "Ordinary voters never took much interest. Perhaps they didn’t care whether they were ruled by a faraway elite in Brussels or ditto in Westminster."

One issue on which debate has foundered has been the 'education gap' - although it is not as clear-cut as first thought and we have to be very wary of sterotyping, as 'the long read' in yesterday's Guardian suggests:

How the education gap is tearing politics apart | David Runciman | Politics | The Guardian

Certainly, the universities are having a very anxious time:

Futures Forum: Brexit: and Exeter University

Futures Forum: Brexit: and Exeter University: and "the huge number of overseas students which makes it one of the leading universities in the country, if not in the world."

As is the science community:

Futures Forum: Brexit: and biotechnology

Futures Forum: Brexit: and ensuring impartial funding for scientific research

Today's Guardian carried further anxious comment from the latest winners of Nobel Prizes:

Brexit 'not good news for British science' warn new Nobel laureates

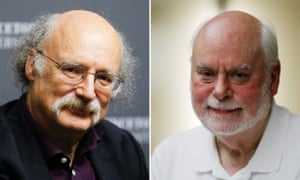

Duncan Haldane and Sir Fraser Stoddart call for scientists to be given protected status for visas, and highlight the role of EU funding in attracting elite scientists

Two British laureates who were awarded Nobel prizes this week have warned that government policies linked to Brexit risk turning elite scientists away from British laboratories.

Duncan Haldane, who was awarded the Nobel prize for physics on Tuesday, said that he had been considering returning to Britain from his post at Princeton University, New Jersey, but that this would be unlikely if access to prestigious research grants from the European Research Council (ERC) was cut off.

“I was seriously considering coming back a few years ago,” he said. “It was suggested it might be possible to get one of these €5m ERC grants. That’s much better support than I can get here. These grants are specifically aimed at bringing established people back. Without that it makes it more difficult for people to come back.”

“I wouldn’t be going back just to kill myself eating high table dinners at a college,” he added. “The ERC made it much more attractive.”

Haldane called for scientists to be given a protected status for visas, although he told the Guardian that he did not share some scientists’ broader fears about a potential future clampdown on immigration in Britain. “There is clearly a need to be able to attract the top scientists and it goes without saying that complicated paperwork is going to put people off,” he said.

A second scientist, Sir Fraser Stoddart, the Scottish chemist who was awarded the Nobel prize on Wednesday, said that government plans to crackdown on immigration could be a deterrent for the best British scientists as well as those from abroad. “I am very disturbed by the talk coming out of the UK at the moment,” he said. “Anything that stops the free movement of people is a big negative for science.”

He said that he has even advised young scientists to consider looking outside the UK in the future, due to fears that British science may enter a period of decline.

“I would have a plan B if I was a young scientist in Britain,” he said. “It’s not going to be good news for British science. There are a lot of things that, particularly as a Scottish person, you can’t make your mind up about. But there’s no doubt in my mind about this. I do feel very strongly about it.”

Haldane’s move the US in the 1980s was prompted by the Thatcher government squeezing funding for curiousity-driven scientific research. “There was a depressing atmosphere in British science at the time because of stupid government ideas that one should do something ‘useful’,” he said.

“They wanted to fund research into turbulence in North Sea gas pipes - an idea that I found pretty depressing.”

Fraser moved from Birmingham to the University of California Los Angeles in 1997, where he succeeded a past Nobel laureate, Donald Cram, in a prestigious chemistry professorship.

In her conference speech in Birmingham on Wednesday, the prime minister cited Britain’s Nobel successes in science as a source of national pride. “[Britain is] a successful country - small in size but large in stature - that with less than 1% of the world’s population boasts more Nobel laureates than any country outside the United States… with three more added again just yesterday – two of whom worked here in this great city.”

UK universities currently get about £1.2 billion research funding a year from the EU. Switzerland and Israel both “buy in” to allow their scientists access to ERC grants, but Swiss participation is in jeopardy because of proposals to limit free movement of EU citizens into the country.

Stoddart said that in his own research group, at Northwestern University, Illinois, he had scientists and students from more than a dozen different countries. “We get on extremely well regardless of background,” he said. “We have this unity based on shared pursuit of science.”

Stoddart said that early in his career, at Sheffield University, he faced some criticism for recruiting from abroad. “I got colleagues saying ‘Don’t you know that our people are better?’” he said. But he argues that recruiting from a wider pool and bringing in talent from abroad raises everyone’s standards - an approach that is now widely accepted in the scientific world.

“When you get people from Messina or Madrid moving to a cold place like Sheffield, they’re serious about science,” he said. “It’s better for everyone.”

Sir Martin Rees, emeritus professor of physics at the University of Cambridge, and the Astronomer Royal, said: “The UK scientific scene is now much stronger than it was [in the 1980s] - thanks in part of the strengthening of science on mainland Europe. But there is a serious risk, aggravated by the tone of Amber Rudd’s deplorable speech on Tuesday, that there will be a renewed surge of defections, weakening UK science and causing us to fail to recoup our investments over the last 20 years.”

A government spokesman said: “This government has been clear that we will make a success of Brexit, including for our world class universities.

“The UK has a long established system that supports, and therefore attracts, the brightest minds, at all stages of their careers. We fund excellent research wherever it is found, and ensure there is the freedom to tackle important scientific questions.

“Leaving the EU means we will be able to take our own decisions about how we deliver the policy objectives previously targeted by EU funding. Over the coming months we will consult closely with stakeholders to review all EU funding schemes, thereby ensuring that all funding commitments serve the UK‘s national interest.”

“The UK has a long established system that supports, and therefore attracts, the brightest minds, at all stages of their careers. We fund excellent research wherever it is found, and ensure there is the freedom to tackle important scientific questions.

“Leaving the EU means we will be able to take our own decisions about how we deliver the policy objectives previously targeted by EU funding. Over the coming months we will consult closely with stakeholders to review all EU funding schemes, thereby ensuring that all funding commitments serve the UK‘s national interest.”

This has been covered across the media:

Chemistry Nobel prize winner says Brexit will be bad for science - Washington Post

Nobel prize winner says UK science is under threat from Brexit, which should ‘go away’ | The Independent

Premios Nobel británicos alertan del peligro del ‘Brexit’ para la ciencia | Internacional | EL PAÍS

Il gagne le Nobel de chimie et fustige Trump et le Brexit

See also:

Futures Forum: Brexit: ProgrExit and the Transition Town movement

And:

Futures Forum: Brexit: and philosophy

.

.

.

No comments:

Post a Comment