Devon county council budget 2018/19 | Barnstaple, Bideford and Ilfracombe News - North Devon Gazette

Council set to spend an extra £19.5m on adult social care, health and children’s services - Devon Live

But it isn't just the Guardian which is concerned about the pressures on social care:

Social care postcode gap widens for older people | Society | The Guardian

The Times is pointing to uncomfortable choices:

We’ll all pay dearly for ignoring social care

ALICE THOMSON

december 13 2017, the times

Politicians don’t want to confront the cost of caring for the elderly but that only makes the burden greater

Pimp my Zimmer is the latest craze among the elderly. With the help of schoolchildren, care home residents have been decorating their walking frames with tinsel, foam bumpers, plastic flowers and knitting, resulting in a 60 per cent reduction in falls in some homes. The grey metal bars are hard for many to see and tricky for people with dementia to recognise. It helps to raise a smile and encourage a helping hand when residents make their way down the high street with their sparkling frames.

British scientists, too, are striving to improve the lot of the frail and elderly. This week a team announced that they have successfully tested a drug that suppresses the rogue gene behind Huntington’s disease, and the method might also…

We’ll all pay dearly for ignoring social care | Comment | The Times & The Sunday Times

This is the view from the BBC following the UK Budget last month - and it shows how councils will continue to struggle:

Have there been two decades of failure to reform social care?

We’ll all pay dearly for ignoring social care | Comment | The Times & The Sunday Times

This is the view from the BBC following the UK Budget last month - and it shows how councils will continue to struggle:

Have there been two decades of failure to reform social care?

By Rachel Schraer BBC News

24 November 2017

Budget 2017

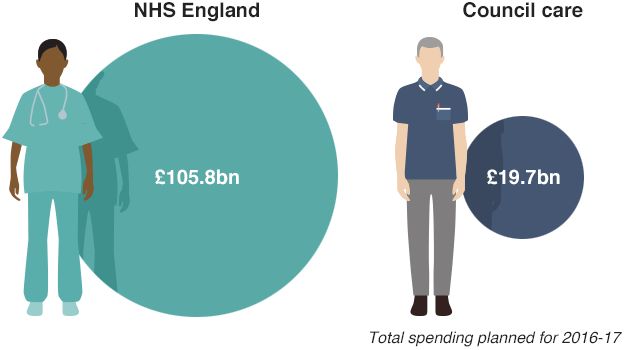

A politically-charged Budget has passed with no mention of social care, despite a growing sense in recent years that the system of support for older people and younger disabled adults is on the point of crisis. Social care can include anything from being cared for in a care home to having someone come into your home to help with washing, dressing and medication. It's paid for by local councils rather than the NHS.

For the past two decades, successive governments have known something needs to be done. They've published at least 300,000 words in formal consultations, policy papers and commissions on the subject. That's nearly two Homer's Odysseys or, if you prefer, three Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stones. It's a lot of words. The figure would be even higher if we included every non-governmental commission, engagement exercise or piece of new guidance.

But despite all this talk, and the huge scale of the problem, little radical change has been made to a system many agree needs to be completely rethought.

Social care is devolved and we're talking about England here. Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland have separate systems, all of which are comparatively more generous than England's.

The prime minister was criticised for proposals dubbed the "dementia tax"

The prime minister was criticised for proposals dubbed the "dementia tax"In 1999, it was proposed that older people should be able to access free personal care, including help with washing, dressing and preparing meals. The recommendation was taken up in Scotland but not in England.

A decade later, Labour got as far as publishing a White Paper - a proposal for future legislation - setting out plans for a National Care Service to run parallel to the NHS, to "meet the needs of people when they need help, free when they need it". But this plan didn't go any further.

Most recently, and perhaps most radically, the 2014 Care Act enshrined in law a cap on care costs meaning no one would pay more than £72,000 over their lifetime, as well as ruling how people's needs should be assessed. But this fundamental change has been shelved, at least until 2020, over concerns about the cost of implementation.

There has been lots of innovation and development at a local level, but centrally we have "essentially got the same method of funding social care as we've had for the last 20 years", according to Simon Bottery of independent health think tank, the King's Fund.

Definitive figure

Millions of people have gone through the social care system over the past decade. Last year, there were 1.8 million requests for social care support - almost a third of which resulted in none being provided, partly because some people were referred to other services.

Between 2001-02 and 2013-14, there were almost 33 million referrals to social care services in England - although some of these will be for the same person. During this period, the way data was collected changed so it's difficult to give a definitive figure for how many people have asked for, and received care, but these numbers give a sense of the scale of activity in the system.

In 2016, Age UK estimated that 1.2 million older people in England were living with unfulfilled social care needs (such as not receiving assistance with bathing and dressing), a rise from 800,000 in 2010.

Almost £170bn in cash was spent by English councils on adult social care over the past 10 years. Councils pay for the services they provide, including social care, using money which they are given from central government through grants, council tax, and other sources like business rates.

Between 2010-11 and 2015-16, overall funding from central government to councils fell by 37% in real terms, according to a Parliamentary report ahead of the March Budget. With less money in the pot, councils are having to spend a higher proportion of their finances on the things they have a legal duty to do - like social care. If someone meets the threshold of need and can't afford their own care, councils must step in.

As a result, adult social care is accounting for a growing proportion of councils' total budgets. In 2010-11, it was 29% of their outgoings, but for some councils it's now approaching half of all their spending. And these growing pressures have led the government to step in with emergency injections of cash three times since 2010, worth £4.6bn in total.

But these emergency payments are seen by many as a sticking plaster - the Local Government Association which represents councils describes them as "one-off funding and not a long-term solution".

There were almost 12 million people over the age of 65 (18% of the population), with 1.5 million of those over 85 (2.4% of the population), living in the UK in 2016 - that's up from 16% and 1.8% respectively 20 years ago. We're living longer, healthier lives but we're also requiring significant care for longer periods of time than before, and this inevitably puts extra strain on the system. In 2009-10, 250,000 over-90s were seen in A&E - by last year this figure was more than 450,000.

There were also a record number of online searches for the term "social care" in the UK in May, just before the general election. Between 1997 and 2007, social care was mentioned in Parliament 5,500 times, according to the official record, Hansard, but between 2008 and 2017, it appeared almost 30,000 times.

The silence on social care in the Budget wasn't a complete surprise - beforehand, the government announced that a long-awaited consultation paper on its future, expected this autumn, would be published next summer instead. The government says an independent panel of experts will consult on establishing a "a long-term, sustainable solution to providing the care older people need". The consultation will only focus on older people, with a parallel consultation on how to fund care for younger disabled adults expected to follow.

So will this consultation deliver what so many have failed to over the past 20 years? At least until next summer, we still don't have the answer.

Have there been two decades of failure to reform social care? - BBC News

.

.

.

No comments:

Post a Comment