Margaret Atwood: Rachel Carson's Silent Spring, 50 years on | Books | The Guardian

How ‘Silent Spring’ Ignited the Environmental Movement - The New York Times

It also inspired the Norwegian philosopher Arne Naess who came up with the idea of 'deep ecology'

What is Deep Ecology? | Schumacher College

Portrait of the Norwegian philosopher Arne Naess and the Deep Ecology Movement. Made in 1997 and shot on location in Naess's hut Tvergastein on the Hardangervidda mountain plateau, and in Berkeley, USA

Arne Naess - video dailymotion

The notion of 'deep ecology' is appearing everywhere today, for example:

Why Karachi is getting too hot to handle

December 17, 2018

Mansoor Raza

It was reported that about 60 people died in the Karachi heat wave of 2018. A few years earlier, in 2015, temperatures up to 49°C led to the deaths of about 1,200 people from dehydration and heat stroke.

The proponents of deep ecology (a thread of philosophical propositions on environmental issues) suggest that a good environmentalist, by default, is anti-establishment, as commercial establishments and governmental set-ups, across the globe are responsible for the environmental woes of the planet. Is Karachi’s recurring heat wave irrefutable evidence of their argument?

Why Karachi is getting too hot to handle

The philosophy of deep ecology is being cited today by the latest activists, as reported by the Ecologist:

'Anonymous for the Voiceless'

Oliver Haynes | 13th December 2018

A closer look at the tactics and philosophy behind a global network of vegan activists.

This day of global activism on 3 November was coordinated by the street action group Anonymous for the Voiceless. An offshoot of the hacktivist movement Anonymous, AV was established in 2016 with the aim of converting people to veganism.

Several of the activists seem to espouse something similar to deep ecology, even if they haven’t read Naess directly. I spoke to three activists at the Paris cube on International Cube Day. They all stated that vegan activism was part of a wider project to end all forms of exploitation; they were all in other movements alongside AV.

'Anonymous for the Voiceless' - The Ecologist

As reported by the City Journal, the house quarterly from the 'leading free market think tank' the Manhattan Institute, 'deep ecology' is not universally welcome:

Green Madness:

The doctrine of deep ecology declares that we must keep our hands off the divine order of nature—even if it kills us.

12 December 2018

The broader notions of deep ecology have made major headway in mainstream thought, especially through the advocacy of influential Greens such as Bill McKibben and David Graeber, who have sounded the alarm for years on global warming, the depredations of fossil fuels, and the evils of human technology. Since the early 1970s, deep ecology has been the beating heart of radical environmentalism. Most people today have never heard of Naess and know nothing about deep ecology, but without knowing it, they have increasingly accepted many of its precepts. With climate change (whether you believe in it or not) destined to be a major policy issue for years to come, along with related issues concerning human interaction with the natural world, it’s worth understanding what the vision of deep ecology entails—and what its practical consequences would be.

Deep ecology is really radical: its two fundamental principles—“self-realization” and “biocentric equality”—amount to a complete rejection of Western modernity. According to deep ecologists Bill Devall and George Sessions, authors of the 1985 book Deep Ecology, self-realization is “in keeping with the spiritual traditions of many of the world’s religions,” but the self of which they speak is quite different from the modern Western version—one based in a notion of individual liberty and self-fulfillment. The ecological self encompasses humanity as a whole and, even more, includes the entire nonhuman world. No one is saved, they say, until all are saved; and the “one” includes me, all human beings, whales, grizzly bears, mountains and rivers, and “the tiniest microbes in the soil.” That’s a big self.

Green Madness: The doctrine of deep ecology declares that we must keep our hands off the divine order of nature—even if it kills us. | Jerry Weinberger, City Journal

Exeter-based therapist Dr Adrian Harris has a blog which looks at these issues:

Environmental philosophy is a complex subject, but clear debate around deep ecology, social ecology, eco-feminism, earth-centered spirituality, ecopsychology, eco-somatics, ethics and similar topics are crucial for our global future.

The Green Fuse for environmental philosophy, deep ecology, social ecology, eco-feminism, earth-centered spirituality

He is not uncritical of the deep ecology movement:

Deep ecology sometimes appears to idealize a the society of indigenous hunter-gatherer tribes, but in reality many primitive tribes are not especially ecocentric. Riane Eisler, author of The Chalice and the Blade writes:

"...many peoples past and present living close to nature have all too often been blindly destructive of their environment. While many indigenous societies have a great reverence for nature, there are also both non-Western and Western peasant and nomadic cultures that have overgrazed and overcultivated land, decimated forests, and where population pressures have been severe, killed off animals needlessly and indifferently."

Deep Ecology Critique on the green fuse

See also:

Futures Forum: On the Transition: "Future Primitive"

What Black Elk Left Unsaid: On the Illusory Images of Green Primitivism on JSTOR

The problem with the debate around what 'deep ecology' stands for is that it gets rather personal:

Monbiot meets the eco fascists

And calling someone or something 'fascist' doesn't help the debate:

Accusations of ecofascism are common but usually strenuously denied.[7][1] Such accusations have come from both those on the political left who see it as an assault on human rights, as in social ecologist Murray Bookchin's use of the term, and from those on the political right, as in Rush Limbaugh and other conservative and wise use movement commentators. In the latter case, it is sometimes a hyperbolic use of the term that is applied to all environmental activists, including more mainstream groups such as Greenpeaceand the Sierra Club.[1]

Ecofascism - Wikipedia

However, the critiques of 'deep ecology' should not be discounted:

In 1987, as the keynote speaker at the first gathering of the U.S.Greens in Amherst, Massachusetts, Bookchin initiated a critique of deep ecology, indicting it for misanthropy, neo-Malthusianism, biocentricism, and irrationalism. A high-profile deep ecologist Dave Foreman of Earth First! had recently said that famine in Ethiopia represented "nature taking its course," nature self-correcting for human "overpopulation."

Murray Bookchin - Wikipedia

And these criticisms are recognised by the movement itself - with this piece from the Foundation for Deep Ecology itself:

Unfortunately, some vociferous environmentalists who claim to support the movement have said and written things that are misanthropic in tone. Supporters of the deep ecology movement are not anti-human, as is sometimes alleged. Naess's platform principle Number 1 begins with recognizing the inherent worth of all beings, including humans. Gandhian nonviolence is a tenet of deep ecology activism in word and deed. Supporters of the deep ecology movement deplore anti-human statements and actions.

Accepting the Deep Ecology Platform principles entails a commitment to respecting the intrinsic values of richness and diversity. This, in turn, leads one to critique industrial culture, whose development models construe the Earth only as raw materials to be used to satisfy consumption and production—to meet not only vital needs but inflated desires whose satisfaction requires more and more consumption. While industrial culture has represented itself as the only acceptable model for development, its monocultures destroy cultural and biological diversity in the name of human convenience and profit.

If we do not accept the industrial development model, what then? Endorsing the Deep Ecology Platform principles leads us to attend to the “ecosophies” of aboriginal and indigenous people so as to learn from them values and practices that can help us to dwell wisely in the many different places in this world. We learn from the wisdom of our places and the many beings who inhabit them. At the same time, the ecocentric values implied by the platform lead us to recognize that all human cultures have a mutual interest in seeing Earth and its diversity continue for its own sake and because most of us love it. We want to flourish and realize ourselves in harmony with other beings and cultures. Is it possible to develop common understandings that enable us to work with civility toward harmony with other creatures and beings? The Deep Ecology Platform principles are a step in this direction. Respect for diversity leads us to recognize the ecological wisdom that grows specific to place and context. Thus, supporters of the deep ecology movement emphasize place-specific, ecological wisdom, and vernacular technology practices. No one philosophy and technology is applicable to the whole planet. As Naess has said many times, the more diversity, the better.

Foundation For Deep Ecology | The Deep Ecology Movement

This is a very critical stance:

Hard green - RationalWiki

With more, thoughtful resources:

Over the last years, several integrative fields of inquiry—such as systems science, resilience science, ecosystem health, ethnoecology, deep ecology Gaia theory, biocultural diversity, among others—have been advancing our understanding of the complex non-linear and multi-scale relationships between people and nature. To better enable us to tackle the multiple challenges facing the planet, our home, many of these fields of inquiry seek to develop respectful and equitable ways of generating knowledge about our relationship with the natural world through braiding traditional knowledge systems and conventional “Western” science.

Braiding Science Together with Indigenous Knowledge - Scientific American Blog Network

And:

A New Future for Nature - RSA and A New Future for Nature - George Monbiot - YouTubeBron Taylor - Exploring and Studying Environmental Ethics & History, Nature Religion, Radical Environmentalism, Surfing Spirituality, Deep Ecology and more...

To finish, here is a seminal article from the former environmentalist campaigner and founder of the Dark Mountain Project:

Dark Ecology

December 2012

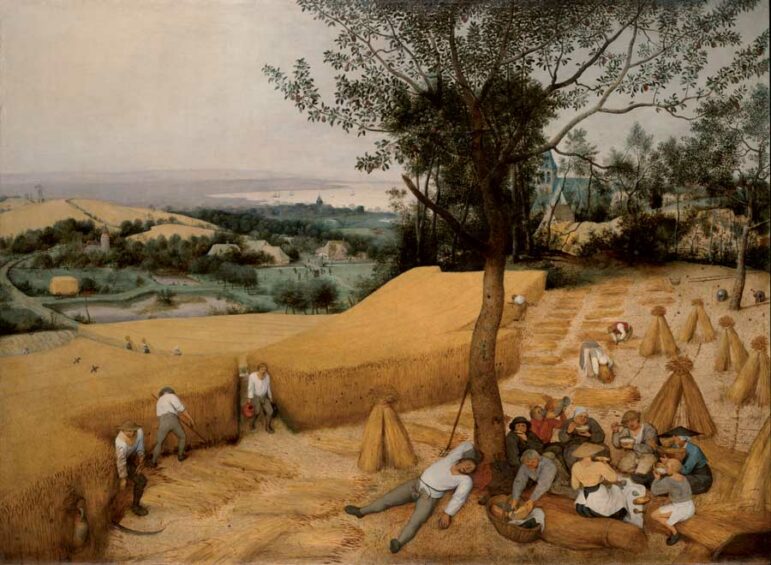

Painting by Pieter Bruegel the Elder

Take the only tree that’s left,

Stuff it up the hole in your culture.

—Leonard Cohen

Retreat to the desert, and fight.

—D. H. Lawrence

THE HANDLE, which varies in length according to the height of its user, and in some cases is made by that user to his or her specifications, is like most of the other parts of the tool in that it has a name and thus a character of its own. I call it the snath, as do most of us in the UK, though variations include the snathe, the snaithe, the snead, and the sned. Onto the snath are attached two hand grips, adjusted for the height of the user. On the bottom of the snath is a small hole, a rubberized protector, and a metal D-ring with two hex sockets. Into this little assemblage slides the tang of the blade.

This thin crescent of steel is the fulcrum of the whole tool. From the genus blade fans out a number of ever-evolving species, each seeking out and colonizing new niches. My collection includes a number of grass blades of varying styles—a Luxor, a Profisense, an Austrian, and a new, elegant Concari Felice blade that I’ve not even tried yet—whose lengths vary between sixty and eighty-five centimeters. I also have a couple of ditch blades (which, despite the name, are not used for mowing ditches in particular, but are all-purpose cutting tools that can manage anything from fine grass to tousled brambles) and a bush blade, which is as thick as a billhook and can take down small trees. These are the big mammals you can see and hear. Beneath and around them scuttle any number of harder-to-spot competitors for the summer grass, all finding their place in the ecosystem of the tool.

None of them, of course, is any use at all unless it is kept sharp, really sharp: sharp enough that if you were to lightly run your finger along the edge, you would lose blood. You need to take a couple of stones out into the field with you and use them regularly—every five minutes or so—to keep the edge honed. And you need to know how to use your peening anvil, and when. Peen is a word of Scandinavian origin, originally meaning “to beat iron thin with a hammer,” which is still its meaning, though the iron has now been replaced by steel. When the edge of your blade thickens with overuse and oversharpening, you need to draw the edge out by peening it—cold-forging the blade with hammer and small anvil. It’s a tricky job. I’ve been doing it for years, but I’ve still not mastered it. Probably you never master it, just as you never really master anything. That lack of mastery, and the promise of one day reaching it, is part of the complex beauty of the tool.

Etymology can be interesting. Scythe, originally rendered sithe, is an Old English word, indicating that the tool has been in use in these islands for at least a thousand years. But archaeology pushes that date much further out; Roman scythes have been found with blades nearly two meters long. Basic, curved cutting tools for use on grass date back at least ten thousand years, to the dawn of agriculture and thus to the dawn of civilizations. Like the tool, the word, too, has older origins. The Proto-Indo-European root of scythe is the word sek, meaning to cut, or to divide. Sek is also the root word of sickle, saw, schism, sex, and science.

I’VE RECENTLY BEEN reading the collected writings of Theodore Kaczynski. I’m worried that it may change my life. Some books do that, from time to time, and this is beginning to shape up as one of them.

It’s not that Kaczynski, who is a fierce, uncompromising critic of the techno-industrial system, is saying anything I haven’t heard before. I’ve heard it all before, many times. By his own admission, his arguments are not new. But the clarity with which he makes them, and his refusal to obfuscate, are refreshing. I seem to be at a point in my life where I am open to hearing this again. I don’t know quite why.

...

Orion Magazine | Dark Ecology

Ecocentrism: a response to Paul Kingsnorth | openDemocracy

Dark Ecology | Paul Kingsnorth | Orion Magazine | The Wildlife News

See also:

The Dark Mountain Project

Why I stopped believing in environmentalism and started the Dark Mountain Project | Environment | theguardian.com

UNCIVILISATION, The Dark Mountain Festival 2010: Paul Kingsnorth, "Time to stop pretending" - YouTube

Uncivilisation 2011 - Looking for Hope in the Dark | Transition Network

Paul Kingsnorth on living with climate change. | Transition Network

Finally, it gets very dark here, from this month's New York magazine, looking at the legacy of Theodore Kaczynski:

The Unlikely New Generation of Unabomber Acolytes

.

.

.

Take the only tree that’s left,

Stuff it up the hole in your culture.

—Leonard Cohen

Retreat to the desert, and fight.

—D. H. Lawrence

THE HANDLE, which varies in length according to the height of its user, and in some cases is made by that user to his or her specifications, is like most of the other parts of the tool in that it has a name and thus a character of its own. I call it the snath, as do most of us in the UK, though variations include the snathe, the snaithe, the snead, and the sned. Onto the snath are attached two hand grips, adjusted for the height of the user. On the bottom of the snath is a small hole, a rubberized protector, and a metal D-ring with two hex sockets. Into this little assemblage slides the tang of the blade.

This thin crescent of steel is the fulcrum of the whole tool. From the genus blade fans out a number of ever-evolving species, each seeking out and colonizing new niches. My collection includes a number of grass blades of varying styles—a Luxor, a Profisense, an Austrian, and a new, elegant Concari Felice blade that I’ve not even tried yet—whose lengths vary between sixty and eighty-five centimeters. I also have a couple of ditch blades (which, despite the name, are not used for mowing ditches in particular, but are all-purpose cutting tools that can manage anything from fine grass to tousled brambles) and a bush blade, which is as thick as a billhook and can take down small trees. These are the big mammals you can see and hear. Beneath and around them scuttle any number of harder-to-spot competitors for the summer grass, all finding their place in the ecosystem of the tool.

None of them, of course, is any use at all unless it is kept sharp, really sharp: sharp enough that if you were to lightly run your finger along the edge, you would lose blood. You need to take a couple of stones out into the field with you and use them regularly—every five minutes or so—to keep the edge honed. And you need to know how to use your peening anvil, and when. Peen is a word of Scandinavian origin, originally meaning “to beat iron thin with a hammer,” which is still its meaning, though the iron has now been replaced by steel. When the edge of your blade thickens with overuse and oversharpening, you need to draw the edge out by peening it—cold-forging the blade with hammer and small anvil. It’s a tricky job. I’ve been doing it for years, but I’ve still not mastered it. Probably you never master it, just as you never really master anything. That lack of mastery, and the promise of one day reaching it, is part of the complex beauty of the tool.

Etymology can be interesting. Scythe, originally rendered sithe, is an Old English word, indicating that the tool has been in use in these islands for at least a thousand years. But archaeology pushes that date much further out; Roman scythes have been found with blades nearly two meters long. Basic, curved cutting tools for use on grass date back at least ten thousand years, to the dawn of agriculture and thus to the dawn of civilizations. Like the tool, the word, too, has older origins. The Proto-Indo-European root of scythe is the word sek, meaning to cut, or to divide. Sek is also the root word of sickle, saw, schism, sex, and science.

I’VE RECENTLY BEEN reading the collected writings of Theodore Kaczynski. I’m worried that it may change my life. Some books do that, from time to time, and this is beginning to shape up as one of them.

It’s not that Kaczynski, who is a fierce, uncompromising critic of the techno-industrial system, is saying anything I haven’t heard before. I’ve heard it all before, many times. By his own admission, his arguments are not new. But the clarity with which he makes them, and his refusal to obfuscate, are refreshing. I seem to be at a point in my life where I am open to hearing this again. I don’t know quite why.

...

Orion Magazine | Dark Ecology

Ecocentrism: a response to Paul Kingsnorth | openDemocracy

Dark Ecology | Paul Kingsnorth | Orion Magazine | The Wildlife News

See also:

The Dark Mountain Project

Why I stopped believing in environmentalism and started the Dark Mountain Project | Environment | theguardian.com

UNCIVILISATION, The Dark Mountain Festival 2010: Paul Kingsnorth, "Time to stop pretending" - YouTube

Uncivilisation 2011 - Looking for Hope in the Dark | Transition Network

Paul Kingsnorth on living with climate change. | Transition Network

Finally, it gets very dark here, from this month's New York magazine, looking at the legacy of Theodore Kaczynski:

The Unlikely New Generation of Unabomber Acolytes

.

.

.

No comments:

Post a Comment