Futures Forum: Brexit: and the Stronger Towns Fund

And not southern less-Brexit-voting towns:

Futures Forum: Brexit: and the Stronger Towns Fund not getting as far as East Devon

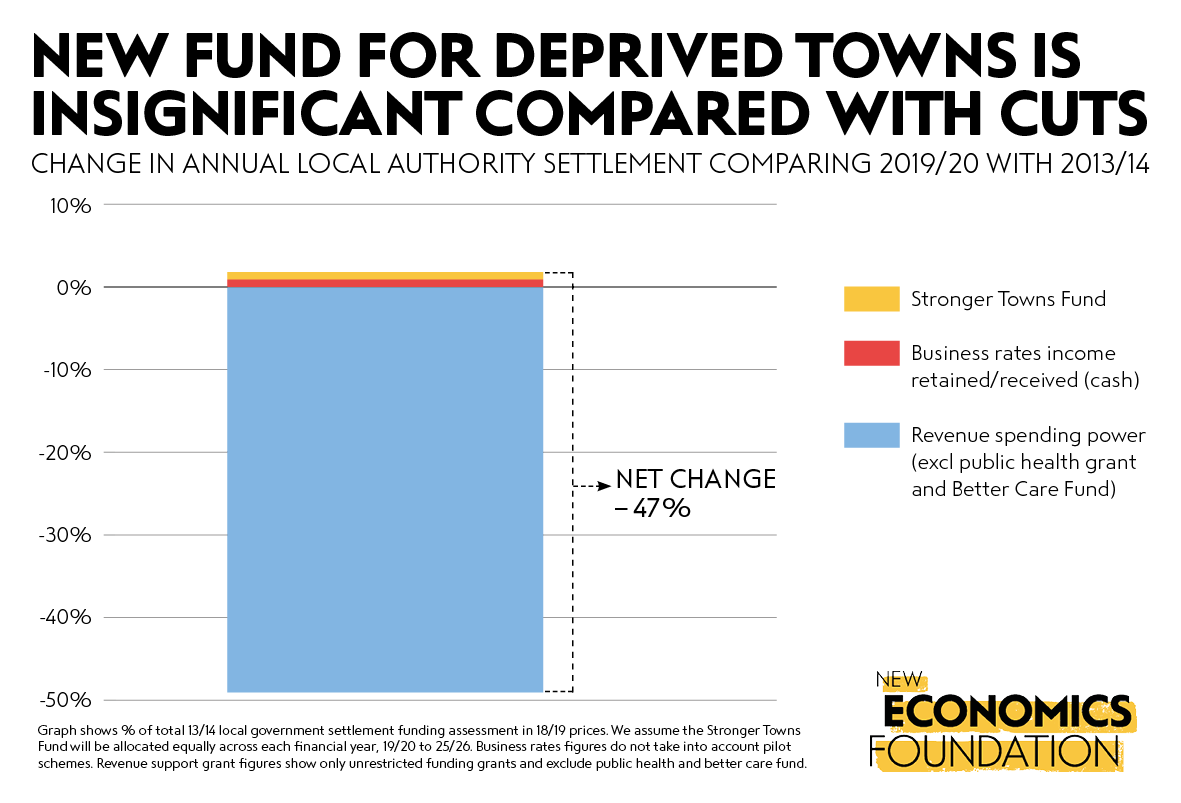

Another complaint is that, actually, the cash being offered is less than the original cuts to local government - and, interestingly, it's the politically neutral local government bodies that are making this point the loudest:

£1.6bn Stronger Towns fund branded 'tokenistic' | News | Local Government Chronicle

Whitehall accused of bribing MPs with 16bn Brexit fund - LocalGov.co.uk - Your authority on UK local government

Elsewhere, the comment is pretty scathing.

This piece from The Conversation is critical of how EU spending has been badly spent in many deprived areas - and asks if the UK government can really do any better:

Is Theresa May’s £1.6 billion fund for English towns enough to rebalance Britain’s skewed economy?

Calvin Jones

Professor of Economics, Cardiff University

March 8, 2019

Whitehall accused of bribing MPs with 16bn Brexit fund - LocalGov.co.uk - Your authority on UK local government

Elsewhere, the comment is pretty scathing.

This piece from The Conversation is critical of how EU spending has been badly spent in many deprived areas - and asks if the UK government can really do any better:

Is Theresa May’s £1.6 billion fund for English towns enough to rebalance Britain’s skewed economy?

Calvin Jones

Professor of Economics, Cardiff University

March 8, 2019

English towns with struggling economies will receive £1.6 billion of funding over six years. The UK government announced the creation of the “stronger towns fund” – the lion’s share of which will be distributed to towns in Northern England and the Midlands. Critics have focused on the fund’s assumed purpose as a “bribe” to gain Labour MPs’ votes for Prime Minister Theresa May’s deal to leave the EU, and on the inadequate size of the pot.

Leaving the first criticism aside, the second certainly has some merit: £1.6 billion sounds a large sum for a single project (at least, for one outside London). But it’s a tiny amount to complete a “transformative” programme of work in many places over a number of years – especially when those places have already lost much more than that during the past decade of austerity, and stand to lose further billions in EU support if and when the UK exits the union.

The difficulties the fund will face have been foreshadowed by the poor performance of EU regeneration funds in Wales. There, £1.6 billion (plus extra funding from UK sources) has been focused on a much smaller area with a much smaller population, from 2014 to 2020. This EU funding builds on similar sized programmes running from 1999 to 2006 and from 2007 to 2013.

Yet these investments in infrastructure, productivity, skills, tourism and research and development have done little to improve the relative prosperity of the targeted area, compared to Wales as a whole – let alone the rest of the UK.

Perhaps without such funding, areas such as the Welsh Valleys in particular might have slipped even further behind. But this recent experience does call in to question whether the stronger towns fund can really bring prosperity to relatively deprived towns in England.

...

Is Theresa May's £1.6 billion fund for English towns enough to rebalance Britain's skewed economy? - The Conversation

The FT also looks at the bigger picture - and also finds the latest central government initiative lacking:

May’s cash bung will not be enough to revive ailing towns

The UK government’s offer of money to poorer areas is welcome, but insufficient

Bronwen Maddox MARCH 8, 2019

It was inevitable that Theresa May’s sudden gift of £1.6bn for poorer English towns would be called a bribe. Coming just before key votes next week that will determine the nature and timing of Brexit, her Stronger Towns Fund cannot shed its apparent political purpose: to persuade Labour MPs in Leave constituencies to back her deal.

The prime minister has said that the cash would go to towns mainly in the Midlands and north of England that had not “shared the proceeds of growth”. She might have continued (though didn’t) to say that resentments of voters in these places, not least at the capital’s glittering supremacy, helped produce the Brexit vote. James Brokenshire, communities secretary, denying that the fund was a Brexit bribe, said it was intended for towns that “felt left behind”, but many of those which might benefit from the fund, like Stoke-on-Trent, Wolverhampton, Wigan and Doncaster, voted heavily to Leave.

Government denials of a Brexit motive provoked derision from some MPs in northern and Midlands constituencies. Labour’s Lisa Nandy and Gareth Snell have said it won’t buy their votes. Others, though, have been cautiously interested. Some hope that Wednesday’s Spring Statement could unlock even more (helped by better than expected tax receipts, which have given Philip Hammond, the chancellor, a fraction more wriggle room).

Tactical as the prime minister’s announcement undoubtedly was, she is not the first to try to devise a way to help struggling parts of the UK. Indeed most governments for years have tried. The question is whether putting money into towns works, and if so, how.

Every politician likes to talk about decentralisation and giving more to the regions — in the run-up to a general election. When elected, they often get less keen on handing over money or the power to raise it. What is good for local democracy isn’t good for central government’s ability to use tax revenue for its own priorities, a quiet truth that has come home to governments of left and right, and a reason why Westminster remains so dominant in UK government.

It is not, though, as if nothing has been tried. Labour created its regional development agencies to give localities the power to decide what development they needed. The coalition government set up the Regional Growth Fund in the acknowledgment that while the south-east was booming, other parts were not. George Osborne’s “northern powerhouse”, which began to take real shape only in his last months as chancellor, came from the same inspiration.

These have had some impact. But they have done little to counterbalance the sustained investment in the south-east — its transport, buildings, and culture — from both government and business. Recent initiatives are also dwarfed by the deep cuts in local government funding since 2010, which have begun to curtail rubbish collection, parks, libraries and social care.

The experience of former mining towns has driven home the point that communities that have suffered a profound shock, such as the loss of their main source of jobs, need help if they are to thrive again. People are not easily going to retrain and move seamlessly into a new sector, as economics textbooks might imply.

But what kind of help? Some of these towns that suffered an old shock now face new ones. High streets — and the jobs in them — are vanishing, shops boarded up or replaced by betting or charity outlets. Manufacturing jobs may have gone overseas or to robots. That is before the disruption Brexit might bring.

It was inevitable that Theresa May’s sudden gift of £1.6bn for poorer English towns would be called a bribe. Coming just before key votes next week that will determine the nature and timing of Brexit, her Stronger Towns Fund cannot shed its apparent political purpose: to persuade Labour MPs in Leave constituencies to back her deal.

The prime minister has said that the cash would go to towns mainly in the Midlands and north of England that had not “shared the proceeds of growth”. She might have continued (though didn’t) to say that resentments of voters in these places, not least at the capital’s glittering supremacy, helped produce the Brexit vote. James Brokenshire, communities secretary, denying that the fund was a Brexit bribe, said it was intended for towns that “felt left behind”, but many of those which might benefit from the fund, like Stoke-on-Trent, Wolverhampton, Wigan and Doncaster, voted heavily to Leave.

Government denials of a Brexit motive provoked derision from some MPs in northern and Midlands constituencies. Labour’s Lisa Nandy and Gareth Snell have said it won’t buy their votes. Others, though, have been cautiously interested. Some hope that Wednesday’s Spring Statement could unlock even more (helped by better than expected tax receipts, which have given Philip Hammond, the chancellor, a fraction more wriggle room).

Tactical as the prime minister’s announcement undoubtedly was, she is not the first to try to devise a way to help struggling parts of the UK. Indeed most governments for years have tried. The question is whether putting money into towns works, and if so, how.

Every politician likes to talk about decentralisation and giving more to the regions — in the run-up to a general election. When elected, they often get less keen on handing over money or the power to raise it. What is good for local democracy isn’t good for central government’s ability to use tax revenue for its own priorities, a quiet truth that has come home to governments of left and right, and a reason why Westminster remains so dominant in UK government.

It is not, though, as if nothing has been tried. Labour created its regional development agencies to give localities the power to decide what development they needed. The coalition government set up the Regional Growth Fund in the acknowledgment that while the south-east was booming, other parts were not. George Osborne’s “northern powerhouse”, which began to take real shape only in his last months as chancellor, came from the same inspiration.

These have had some impact. But they have done little to counterbalance the sustained investment in the south-east — its transport, buildings, and culture — from both government and business. Recent initiatives are also dwarfed by the deep cuts in local government funding since 2010, which have begun to curtail rubbish collection, parks, libraries and social care.

The experience of former mining towns has driven home the point that communities that have suffered a profound shock, such as the loss of their main source of jobs, need help if they are to thrive again. People are not easily going to retrain and move seamlessly into a new sector, as economics textbooks might imply.

But what kind of help? Some of these towns that suffered an old shock now face new ones. High streets — and the jobs in them — are vanishing, shops boarded up or replaced by betting or charity outlets. Manufacturing jobs may have gone overseas or to robots. That is before the disruption Brexit might bring.

...

May’s cash bung will not be enough to revive ailing towns | Financial Times

The New Economics Foundation doesn't pull its punches:

DEPRIVED TOWNS FUND IS INSIGNIFICANT COMPARED WITH STAGGERING CUTS

REVERSING THE DAMAGE DONE BY AUSTERITY WILL TAKE MORE THAN THIS PALTRY OFFER

05 MARCH, 2019 |

SARAH ARNOLD

ANDREW PENDLETON

The Stronger Towns Fund, announced by the government yesterday, is a £1.6 billion fund to be spent between now and 2025 on places that are often referred to as ‘left behind’.

£1.6 billion as a lump sum is not to be sniffed at, even though in government spending terms it’s relatively small beer. Share small beer out over seven years and it’s reduced to a thimble full; around £267 million total per year if spending starts in the financial year 2019/20 and is distributed evenly until 2025/26. Share it out further to all the places in the UK that most need government investment, training and jobs and it’s a droplet in the ocean.

If that were the beginning and end of it, then fine. ‘Government announces small bit of funding for something that needs a bigger bit of funding’ is not much of a story. However, the government is giving with one hand, and taking much more away with the other.

The Revenue Support Grant is given to local authorities by central government and makes up around a third of councils’ budgets. Between 2018/19 and 2019/20, the grant is due to be cut by 37% — that’s £1.3 billion in a single year — on top of savage cuts to it that have already taken place.

From 2013/14 to 2019/20, even with locally retained business rates and the main government unrestricted grant, local authorities have seen their net incomes decrease by 48%. The year of Stronger Towns Funding that will presumably occur in 2019/20 (if allocated equally over six years) compensates this loss by less than 1%. Council incomes will still have been cut by 47%. The whole Stronger Towns pot of money would reduce this loss by no more than 5% if provided in one year — which will not be the case. Of course, some regions will receive more than this and others less, but compared to the staggering cuts to local authorities, the new fund pales in comparison.

Aside from this loss of government money, post-Brexit the UK will be losing money provided by the European Union via its structural funds. Between 2014 and 2020, the UK will have received €17.2 billion for regional and social development, which has flowed significantly to many of the same areas that the Stronger Towns Fund will prioritise.

If the UK were to remain in the EU, between 2021 and 2027, €13 billion of EU structural funds would flow to poorer regions; significantly more than the Stronger Towns Fund. Some further settlement is expected from central government to compensate areas for this loss, but the amount is still unclear.

The Stronger Towns Fund has not gone down well in many of the regions, smaller cities and towns at which it will be targeted. And why should it? One cause of the economic malaise many of these places face is austerity. Reversing its effect will take more than this paltry offer. It will take a transformational approach to government investment, focused both on rebalancing the economy and restoring basic public services that are often the lifeblood of communities.

Many, including opposition politicians, have suggested that the Stronger Towns Fund looks like a bribe to persuade Labour MPs in leave-voting constituencies in particular to support the government’s Withdrawal Agreement. If so, the chances are it will have the opposite effect.

Deprived towns fund is insignificant compared with staggering cuts | New Economics Foundation

.

.

.

No comments:

Post a Comment