Futures Forum: Climate change... "Clean growth is a safe bet in the climate casino"

Whilst there is the opposite idea of 'no-growth':

Futures Forum: Steady-state economy... Post-growth economy

... another idea is to 'decouple' growth from its impact on the environment:

Futures Forum: Climate Change solutions: "Revealing greater agreement than the pro-growth versus de-growth dichotomy suggests."

The UN produced a report in 2011 - but many questioned its premise:

The Odd Coupling: Asking the Wrong Questions about “Decoupling” Environmental Impacts from Economic Growth

The rationale for decoupling GDP is summarized in the 2011 United Nations Environmental Programme report, Decoupling Natural Resource Use and Environmental Impacts from Economic Growth:

Decoupling at its simplest is reducing the amount of resources such as water or fossil fuels used to produce economic growth and delinking economic development from environmental deterioration. For it is clear in a world of nearly seven billion people, climbing to around nine billion in 40 years’ time that growth is needed to lift people out of poverty and to generate employment for the soon to be two billion people either unemployed or underemployed.

Critics of economic growth have pointed out that even though relative decoupling of resource use from GDP has always been characteristic of industrial society, absolute decoupling – in which the amount of resource consumed actually decreases, even as the market economy continues to grow – has never happened. The Sustainable Development Commission’s report, Prosperity Without Growth, for example, explained that greater efficiency in resource use also saves money and that money gets spent on even more goods and services resulting in a rebound effect, also known as the Jevons Paradox. “In short, relative decoupling sometimes has the perverse potential to decrease the chances of absolute decoupling.”

But asking whether relative decoupling of GDP from resource consumption can eventually result in absolute decoupling is asking the wrong question. As the decoupling.report clearly indicated, GDP growth is not advocated as an end per se but as a means of generating employment.

Although GDP growth and employment are indeed highly correlated, the growth rate of GDP among the industrially developed countries (OECD) between 1991 and 2009 was about three times as fast as the growth rate of employment. To put this in perspective, energy consumption in the OECD countries increased over the last two decades at roughly the same pace as employment. In other words there has been virtually no relative decoupling of energy consumption and employment in the wealthier countries.

Globally the situation is even worse. From 1991 to 2009 world GDP increased by 93 percent. Employment increased by 33 percent and energy consumption increased by 36 percent. So even though energy consumption per dollar of GDP fell by nearly 30 percent over that period, energy consumption per employed person increased by two and a half percent. If the purpose of GDP growth is job creation, it makes absolutely no sense to talk about the energy intensity of GDP while ignoring the energy intensity of jobs.

As Thomas Pynchon wrote in Gravity’s Rainbow, “If they can get you asking the wrong questions, they don’t have to worry about answers.” What happens when we start asking the right questions? “When we try to pick out anything by itself,” John Muir wrote in My First Summer in the Sierra, “we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe.” Industrial jobs are hitched to energy consumption which is hitched to GHG emissions. The right question, then, is how can we unhitch human flourishing from natural resource consumption and environmental impacts?

The Odd Coupling: Asking the Wrong Questions about “Decoupling” Environmental Impacts from Economic Growth | ECC 2013 – Communication Platform

Decoupling Natural Resource Use and Environmental Impacts from Economic Growth report - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

There is some stimulating 'thinking-outside-the-box' - for example, from the provocatively-named 'Post-Autistic Economics Movement':

Post-autistic economics - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

From their latest paper:

Evaluating the costs of growth: Asad Zaman: download pdf

Climate change, carbon trading and societal self-defence: Max Koch: download pdf

For more such provocative thinking, there is the 'Make Wealth History' foundation...

... which has of late been considering the idea of 'decoupling growth':

Growth and the endless war on carbon

October 1, 2014

Last week I wrote about the New Climate Economy report and its confidence in the compatibility of economic growth and a safe climate. I suggested that politicians and the media were hearing what they wanted to hear without actually reading the report, because it doesn’t actually promise to halt climate change. But there’s another thing that goes unnoticed when you try to fight climate change while growing the economy – you commit yourself to an endless war on carbon.

That’s because until they are disconnected from each other, more growth means more carbon. If the economy is growing, then it is constantly clawing back any progress on cutting emissions. The proposed solution is decoupling growth and emissions through carbon productivity – making more money for each tonne of emissions. But you have to pursue efficiency faster than the economy is growing, otherwise you’re just running on the spot. This is the difference between relative decoupling and absolute decoupling, a crucial distinction that is glaringly absent from the New Climate Economy paper.

Fighting climate change while growing the economy is to be content to constantly take two steps forward and one step back – and bear in mind that we’re currently taking one step forward and two back, since absolute emissions are still growing.

Not only that, but you have to keep doing it indefinitely. Ongoing growth without destabilising the climate requires a constant industrial revolution, a permanent war footing, because every year you have to take more carbon out of the economy to compensate for the growth.

The New Climate Economy admits as much. Their study runs up to 2030, and they suggest that the carbon productivity of the global economy needs to improve by around 3-4% a year, every year to 2030. But there’s no transition, no ‘arrival’ at a safe place by 2030. Quite the opposite:

“In 2030–2050, the improvement in carbon productivity would need to accelerate again, to around 6–7% per year, to stay on track.”Or later in the same report:

“The low-carbon transition will not end in 2030. Much deeper reductions will be required in later years, to take global emissions down to less than 20 Gt CO2e by 2050 and near zero or below in the second half of the century.”McKinsey’s Carbon Productivity Challenge, which also argues for growth, has the same problems. They argue that the carbon productivity of the economy has to increase tenfold between now and 2050. This would be an epic transformation of the economy “comparable in magnitude to the labour productivity of the Industrial Revolution”, but carried out in a third of the time. But since they don’t expect growth the stop in 2050, even a monumental achievement like that wouldn’t be the end of the transition.

Neither report mentions the future beyond 2050, perhaps because the further ahead you think –2080, 2100 – the more absurd the maths becomes. Since the pro-growth reports don’t run with it, here’s Tim Jackson:

“Beyond 2050, of course, if growth is to continue, so must efficiency improvements. With growth at 2% a year from 2050 to the end of the century, the economy in 2100 is 40 times the size of today’s economy. And to all intents and purposes, nothing less than complete decarbonisation of every single dollar will do to achieve carbon targets.”

And that’s at 450 ppm of CO2. If we take 400 or 350 ppm as the safe point, “by 2100 we will need to be taking carbon out of the atmosphere. The carbon intensity of each dollar of economic output will have to be less than zero.” At this point, once we require efficiency rates of 100% or greater, we’re off into the world of perpetual motion machines and alchemy.

This is why the transition to a post-growth economy is so important to the transition beyond carbon. With a post-growth economy, we can genuinely transition – there is a safe place to aim for on the other side. That is not true of the mainstream vision of growth. With endless economic growth comes an endless war against carbon emissions, and ultimately a war with the laws of physics.

Growth and the endless war on carbon | Make Wealth History

References were made to the following, from earlier in the year:

Sustainable growth is not scientifically credible

February 18, 2014

One of the regular objections to those who say that

sustainability is incompatible with economic growth is that it is a

political or ideological stance. We somehow want things to be simpler

and greener and are only too happy to sacrifice a capitalist system that

we disapprove of anyway.

This is a convenient but entirely unfounded accusation.

It’s a matter of maths. Calculate the levels and rate of decarbonisation

required to stabilise the climate, and there is simply no way it can be

achieved in an economy that is growing.

I’ve written about these calculations before. They’re in Tim Jackson’s book Prosperity Without Growth, in nef’s report Growth Isn’t Possible, and (albeit inadvertently) McKinsey’s Carbon Productivity Challenge. Here’s another from Post Carbon Pathways.

In a paper that explores the Environmental Kuznets

Curve, the rebound effect and decoupling, Samuel Alexander explains just

what would need to happen to deliver sustainability if the global

economy continues to grow.

Throughout the last century, developed countries grew at

an average of 3% a year. Growing at this rate, their economies doubled

in size every 23 years. If this exponential growth continues, then by

2080 the developed world’s economies will be 8 times larger than they

are today.

If we continue with the prevailing development model,

then we should expect developing countries to have ‘caught up’ by 2080

too. That means all ten billion people on the planet will be enjoying a

developed world lifestyle. In which case, says Alexander, “the global

economy would be around 80 times larger, in terms of GDP, than the size

of the developed world’s aggregate economy today.”

Stop and look around at the state of the world after

providing a consumerist lifestyle to just one billion people. We’re

already pushing at the limits of what the atmosphere, the nitrogen cycle

and the earth’s biodiversity can handle – can we really crank up

economic activity by a factor of 80?

Of course, the idea is that efficiency runs ahead of

growth so that we meet climate targets without having to decrease GDP –

except that no country has ever achieved absolute decoupling of carbon

emissions and GDP growth. As Jackson calculates, growth to 2050 would

need to be accompanied by carbon efficiency gains of 11% a year – and

the best anyone has ever done is 0.7%.

The maths is not on the side of growth. And yet, the

enduring myth even among many environmentalists is that GDP growth can

continue alongside decarbonisation. This, as Alexander says, “is not a

scientifically credible position.”

Sustainable growth is not scientifically credible | Make Wealth History

This appeared two years ago:

This appeared two years ago:

The challenge of absolute decoupling

August 7, 2012

One of the compromises between the environment and

politics is the term ‘green growth’. It’s always turning up in

government papers or the documents like the UN’s recent Rio +20 agreement.

Green growth is an attempt to turn big environmental problems into

opportunities for greater prosperity. If you get it right, you can carry

on growing the economy while solving the environmental crisis at the

same time… in theory.

For that to happen, you need decoupling.

So far, growing economies also have growing consumption of materials,

growing energy needs and growing CO2 footprints. To grow without

damaging the environment, you need to ‘decouple’ the economy from its

ecological impact. You can do that by moving from heavy industry to

services, using renewable energy, recycling or increasing energy and

material efficiency.

Of course if the economy is growing, then your

efficiency gains have to happen faster than the growth, otherwise the

new growth just swallows up any gains. If the economy is 10% more

efficient than it was a decade ago, but is also 10% larger, then you’re

running to stand still. That’s the difference between absolute

decoupling and relative decoupling. To actually reduce CO2, energy and

material use, the actual amounts we use need to fall in absolute terms.

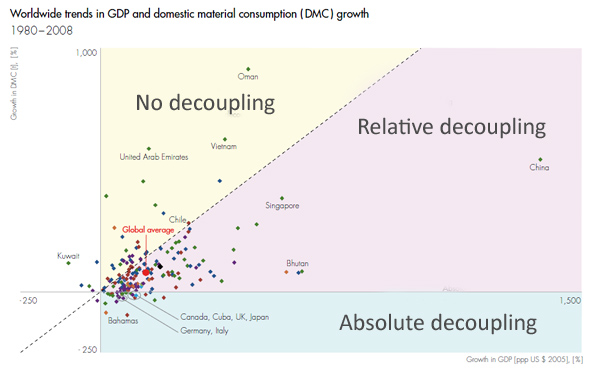

The graph at the top shows the challenge. (It’s from SERI’s recent report on materials consumption here).

The world’s countries are plotted with growth in GDP along the

horizontal axis and growth in materials consumption on the vertical

axis. If a country falls along the horizontal line in the middle, then

its material use and GDP have grown at exactly the same rate. Anywhere

below the horizontal shows that you’re making some efficiency gains, but

that your overall growth is running ahead of them. Only those countries

that are in the blue sector at the bottom have achieved true

decoupling, reducing the amount of timber, fossil fuels and metals that

they use in absolute terms.

The first thing to notice is that the right hand side of

that blue segment is empty – absolute decoupling can only happen in

low-growth countries. The other thing to remember is that even those

consumer economies that did see absolute decoupling – Canada, Italy,

Japan, Germany and the UK – still might not have achieved the holy grail

of green growth. They may have simply displaced their materials use

elsewhere by importing things they used to produce themselves. A quick

glance at imports from China will tell you where materials consumption

in Britain went.

We’re going to hear a lot more about green growth, and

about decoupling. It’s harder than it looks, and in the long term it’s

impossible. Ultimately, we’re not going to get anywhere until we start

questioning growth itself.

The challenge of absolute decoupling | Make Wealth History

To return to the basic question:

Prosperity Without Growth, by Tim Jackson

December 3, 2009“Questioning growth is deemed to be the act of lunatics, idealists and revolutionaries” Tim Jackson warned in his report for the Sustainable Development Commission earlier this year. Fortunately he remains undaunted, and the report has been expanded and released as a book: Prosperity Without Growth – Economics for a finite planet.

As you may have noticed, the response to the financial crisis has been to try to restore the status quo as soon as possible, returning us the pattern of steady growth that we had become accustomed to and that our capitalist model demands. ‘Stability – Growth – Jobs’ said the banner at the G20 summit. The problem is that in the longer term, stability and growth are incompatible. “An economy predicated on the perpetual expansion of debt-driven materialistic consumption is unsustainable ecologically, problematic socially, and unstable economically” writes Jackson.

The book goes on to elucidate three fundamental reasons why the growth model of economics is impossible to sustain. Firstly, it assumes that material wealth is an adequate measure of prosperity, when it is actually pretty obvious that a life worth living is much more complicated than that. Slaves to rising GDP, we sacrifice community and wellbeing in the hope that just a little more, and just a little bit more after that, will make everything alright. This is futile. The growth model is now undermining our happiness and causing a ‘social recession’. “Our technologies, our economy and our social aspirations are all mis-aligned with any meaningful definition of prosperity”

Secondly, growth is unevenly distributed, and so is doomed to fail at providing a basic standard of living for everyone. Globally, the richest fifth of the world takes home 74% of the income, while the poorest fifth gets just 2%. Since poverty is relative, growth will never fix it. It’s a mathematical impossibility. You could grow the world economy for a million years and still not make poverty history.

And that brings us to point number three – we obviously can’t grow the economy for a million years. We’ve already gone into ecological overshoot. “We simply don’t have the ecological capacity” says Jackson. “By the end of the century, our children and grandchildren will face a hostile climate, depleted resources, the destruction of habitats, the decimation of species, food scarcities, mass migrations and almost inevitably war.”

...

Prosperity Without Growth, by Tim Jackson | Make Wealth History

.

.

.

No comments:

Post a Comment