Roads Were Not Built For Cars

Of course, asphalt has been around for much longer than bicycles:

Asphalt - history - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Macadam - road building in America!

Whilst today the use of asphalt is somewhat controversial:

Futures Forum: Alternatives to asphalt for building roads ..... gravel, or ..... concrete, or ..... glass as solar panels

Futures Forum: Climate change: asphalt and urban heat islands

However, the push for 'better roads' a century ago came from the cycling lobby:

19th century cyclists paved the way for modern motorists' roads | Carlton Reid | Environment | The Guardian

... asphalt in general pre-dated the advent of motorcars (asphalt’s use as a road material goes back into antiquity) and the widespread use of it was promoted by the Road Improvements Association. The RIA’s trials of asphalt were led by an official from the Cyclists’ Touring Club and the RIA wasn’t created by a motoring group, it was founded by cyclists, twenty years before motorcars came along. The Road Improvements Association was founded by the National Cyclists’ Union (which later became British Cycling) and the Cyclists’ Touring Club (which later became just CTC).

Roads Were Not Built For Cars | Northern England’s cycle infrastructure is the best in Europe

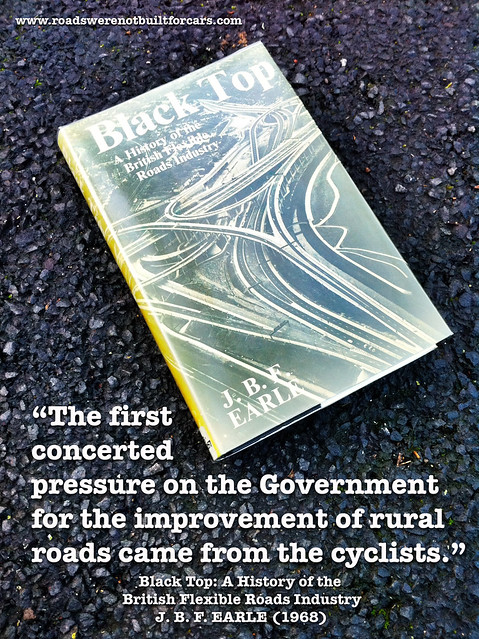

As admitted by the aggregates industry back in the 1960s:

Roads Were Not Built For Cars | Tarmac exec said cyclists were the first to push for improved roads

The British were, it seems, pioneers in this - although by now we have some of the worst facilities for cyclists - for example:

Cycle Facility of the Month

| >> |

Cycle Proofing

|

Cycle Facility of the Month

A big name in cycling has called for councils to 'take note':

Hans Rey on Twitter: "Interesting read "Road Were Not Built For Cars" by @carltonreid http://t.co/1dcFdjW0JJ City councils should take note http://t.co/B8jaVirMTr"

In which case, the hope is that the interest in this book will go beyond the bike-brigade:

Roads Were Not Built For Cars by Carlton Reid review | road.cc

The Secret History of Cars Begins With Bicycles - CityLab

A meticulously researched demolition job on petrolhead myths of road ownership

In 2013, Jeremy Clarkson surprised viewers of Top Gear by declaring: “I bought a bicycle.” Then he told them he’d also bought a T-shirt to wear while riding his new possession and held it up to display its logo: “Motorists: Thank you for letting me use your roads.”

I know I’ve unduly flattered that “joke” by repeating it, but it sums up the philosophy Carlton Reid demolishes so effectively. This book is a closely argued, meticulously researched retort to all those Mr Toads who not only think that they own the roads, but also that they’ve always done so and that everyone else uses them on sufferance.

His starting point is so obvious it possibly doesn’t need to be stated even to the Clarksons of this world. There were plenty of roads before cars came along, and originally cars were seen as the interlopers. MP Sir Ernest Soares told parliament in 1903: “Motorists are in the position of statutary trespassers on the road … roads were never made for motor-cars. Those who designed them and laid them out never thought of motor-cars.”

Roads Were Not Built for Cars by Carlton Reid – review | Books | The Guardian

To finish:

Carlton Reid himself writing over a year and a half ago, not yet anticipating the impact of his book:

How roads were not built for cars

Carlton Reid Tuesday 16 April 2013

A history of how 19th-century cyclists paved the way for modern roads offers clues to how cars could again lose their dominance

Hanover Street in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, originally built for horses and carts. Photograph: Carlton Reid Carlton Reid/Carlton Reid

Even the BBC has called me it, so it must be true. Back in 2011 when I wrote this piece for the Guardian I was merely a journo-with-a-book-idea; now I'm a historian. Two years ago on this very blog I wrote:

Many motorists assume that roads were built for them. In fact, cars are the johnny-come-latelies of highways.

I went on to explain a little bit more about my highway history revisionism.

At the time I didn't have a book title. I do now. The title – Roads Were Not Built For Cars – popped into my head, naturally enough, when I was cycling. A bunch of cars were parked on the pavement and a bunch more were clogging up the road ahead. "It's not as though roads were even built for cars," I mused, and I'm pretty sure my eyebrows must have been knotted and my lips pursed as I was thinking this.

Rewind. I used a couple of words that may need a little explaining. The first is pavement. As my book is about American highway history as well as British, I've trained myself to use pavement in its technical sense. When Americans – and British road engineers – talk about pavement, they mean the road, not the, er, sidewalk. Pavement is a colloquialism. The correct, legal term is footway. Mind you, in everyday speech, I continue to use pavement, especially when confusing Americans: "That's right, in England, bicycles aren't allowed on the pavement."

The second word I'd like to draw attention to is revisionism. This isn't used pejoratively; revisionism is history. Pulitzer Prize winning historian James McPherson, writing for the American Historical Association, said this of revisionism:

There is no single, eternal, and immutable 'truth' about past events and their meaning. The unending quest of historians for understanding the past – that is, 'revisionism' – is what makes history vital and meaningful.

Roads Were Not Built For Cars is therefore a proudly revisionist work, and, like all history, really, it's revisionism with an agenda. The agenda is plain: I want motorists to think before they say or think, "Get off the road, roads are for cars." Not all do, of course, but there's enough out there to make life difficult for cyclists. The belief that roads were made for motorists is almost as old as motoring.

Cyclists were written out of highway history by the all-powerful motor lobby in the 1920s and 1930s. But not all parts of the modern-day motor lobby buy into this history. Edmund King, president of the Automobile Association, was one of the first supporters of my book.

For the book's blurb, King said:

Some drivers think that they own the road so might be surprised when they hear that roads were not built for cars. [This] fascinating insight into the origin of roads hopefully will break down some of the road 'ownership' issues and help promote harmony for all road users whether on four wheels or two.

Motoring owes a great deal to cycling, something that will clearly come as a surprise to many motorists. In a video I produced to promote the book, I asked passers-by to tell me when a busy four-lane highway, in my home town of Newcastle, might have been built, and whom for. The answers boiled down to "the 1950s" and "old cars." Jesmond Road might look and feel like an urban motorway – it's a hostile place to ride a bike, or even walk beside – but it was built to the current width in 1838 and was only later retrofitted for cars. In the 1950s the road was dominated by trams, and not yet strangulated by privately owned cars.

In a strange way, this relatively recent history of the road gives me hope. If you'd have asked a Brit in the 1920s what form of transport would be dominating the streets 60 and 70 years in the future, not many people would have said hoverboards or that other fantastical luxury contraption, the motorcar. People would likely have said "trams".

In the 1890s people would have said bicycles, trains and, thanks to futurists such as HG Wells, mechanical footways (the first one was built for the 1893 World's Fair in Chicago). If the past is a different country, the future can often be more alien. The theory of Peak Car points to a future with a reduced need for those ugly, disfiguring ring roads that blight our cities (it was announced earlier this month that Leicester is to turn part of one of its motor-myopic gyratories into a two-way bike lane).

It's a happy coincidence that the author of the Get Britain Cycling report, due to be launched in a parliamentary reception on 24th April, is Professor Phil 'Peak Car' Goodwin. In a series of influential articles for Local Transport Today in 2010 (paywall), Professor Goodwin wrote:

If rail, bus and tram use all peaked and then declined, so why do so many people assume that car use will either keep rising indefinitely or reach saturation and a 'steady state' condition?

A linked editorial by Dave du Feu of Spokes, the Lothian Cycle Campaign, argued (paywall):

If urban traffic is falling, let's give more space to cyclists.

Such provision would be both healthy and historically correct. It was cyclists, and not motorists, who first pushed for high-quality, dust-free road surfaces (dust was a major irritant at the time, believed to be a cause of disease, especially as so much of it was powdered horse shit). The Roads Improvement Association of the UK was created in 1885 by the Cyclists' Touring Club and the forerunner to British Cycling, ten years before the first motorcar was imported into the country. And in America, the Good Roads movement, started by cyclists, later led to the creation of the US Department of Transportation and many "motor lobby" organisations were, originally, started by cyclists.

To make sure petrolheads don't throw down the book in horror, I've included lots of automotive history. Many automobile pioneers were cyclists before becoming motorists. A surprising number of the first car manufacturers were also cyclists, including Henry Ford. Some carried on cycling right through until the 1940s. For instance, Lionel Martin, who co-founded the Aston Martin marque, favourite of both Clarkson and Bond, James Bond, was a racing tricyclist to his dying day. Literally. He was killed after being hit...by a motorcar.

There will be nugget after revisionist nugget like this and the book, due in August, is already doing rather well. After three-and-a-bit weeks of crowd-funding on Kickstarter the book is triple the original target. Amazingly, it has raised £14,100 in pre-orders, with another 5 days to go. And pledges of cash keep on coming despite the fact the full text for the book will be given away free on the blog-of-the-book.

Why free? There's no point producing a revisionist history and then letting it fester, unseen. By giving it away free I'm hoping a few of the salient facts make it into the mainstream. This mainstream is a motoring mainstream right now. The future could be one where bikes rule the road, just as they did in the 1890s.

How roads were not built for cars | Carlton Reid | Environment | The Guardian

.

.

.

Hanover Street in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, originally built for horses and carts. Photograph: Carlton Reid Carlton Reid/Carlton Reid

Even the BBC has called me it, so it must be true. Back in 2011 when I wrote this piece for the Guardian I was merely a journo-with-a-book-idea; now I'm a historian. Two years ago on this very blog I wrote:

Many motorists assume that roads were built for them. In fact, cars are the johnny-come-latelies of highways.

I went on to explain a little bit more about my highway history revisionism.

At the time I didn't have a book title. I do now. The title – Roads Were Not Built For Cars – popped into my head, naturally enough, when I was cycling. A bunch of cars were parked on the pavement and a bunch more were clogging up the road ahead. "It's not as though roads were even built for cars," I mused, and I'm pretty sure my eyebrows must have been knotted and my lips pursed as I was thinking this.

Rewind. I used a couple of words that may need a little explaining. The first is pavement. As my book is about American highway history as well as British, I've trained myself to use pavement in its technical sense. When Americans – and British road engineers – talk about pavement, they mean the road, not the, er, sidewalk. Pavement is a colloquialism. The correct, legal term is footway. Mind you, in everyday speech, I continue to use pavement, especially when confusing Americans: "That's right, in England, bicycles aren't allowed on the pavement."

The second word I'd like to draw attention to is revisionism. This isn't used pejoratively; revisionism is history. Pulitzer Prize winning historian James McPherson, writing for the American Historical Association, said this of revisionism:

There is no single, eternal, and immutable 'truth' about past events and their meaning. The unending quest of historians for understanding the past – that is, 'revisionism' – is what makes history vital and meaningful.

Roads Were Not Built For Cars is therefore a proudly revisionist work, and, like all history, really, it's revisionism with an agenda. The agenda is plain: I want motorists to think before they say or think, "Get off the road, roads are for cars." Not all do, of course, but there's enough out there to make life difficult for cyclists. The belief that roads were made for motorists is almost as old as motoring.

Cyclists were written out of highway history by the all-powerful motor lobby in the 1920s and 1930s. But not all parts of the modern-day motor lobby buy into this history. Edmund King, president of the Automobile Association, was one of the first supporters of my book.

For the book's blurb, King said:

Some drivers think that they own the road so might be surprised when they hear that roads were not built for cars. [This] fascinating insight into the origin of roads hopefully will break down some of the road 'ownership' issues and help promote harmony for all road users whether on four wheels or two.

Motoring owes a great deal to cycling, something that will clearly come as a surprise to many motorists. In a video I produced to promote the book, I asked passers-by to tell me when a busy four-lane highway, in my home town of Newcastle, might have been built, and whom for. The answers boiled down to "the 1950s" and "old cars." Jesmond Road might look and feel like an urban motorway – it's a hostile place to ride a bike, or even walk beside – but it was built to the current width in 1838 and was only later retrofitted for cars. In the 1950s the road was dominated by trams, and not yet strangulated by privately owned cars.

In a strange way, this relatively recent history of the road gives me hope. If you'd have asked a Brit in the 1920s what form of transport would be dominating the streets 60 and 70 years in the future, not many people would have said hoverboards or that other fantastical luxury contraption, the motorcar. People would likely have said "trams".

In the 1890s people would have said bicycles, trains and, thanks to futurists such as HG Wells, mechanical footways (the first one was built for the 1893 World's Fair in Chicago). If the past is a different country, the future can often be more alien. The theory of Peak Car points to a future with a reduced need for those ugly, disfiguring ring roads that blight our cities (it was announced earlier this month that Leicester is to turn part of one of its motor-myopic gyratories into a two-way bike lane).

It's a happy coincidence that the author of the Get Britain Cycling report, due to be launched in a parliamentary reception on 24th April, is Professor Phil 'Peak Car' Goodwin. In a series of influential articles for Local Transport Today in 2010 (paywall), Professor Goodwin wrote:

If rail, bus and tram use all peaked and then declined, so why do so many people assume that car use will either keep rising indefinitely or reach saturation and a 'steady state' condition?

A linked editorial by Dave du Feu of Spokes, the Lothian Cycle Campaign, argued (paywall):

If urban traffic is falling, let's give more space to cyclists.

Such provision would be both healthy and historically correct. It was cyclists, and not motorists, who first pushed for high-quality, dust-free road surfaces (dust was a major irritant at the time, believed to be a cause of disease, especially as so much of it was powdered horse shit). The Roads Improvement Association of the UK was created in 1885 by the Cyclists' Touring Club and the forerunner to British Cycling, ten years before the first motorcar was imported into the country. And in America, the Good Roads movement, started by cyclists, later led to the creation of the US Department of Transportation and many "motor lobby" organisations were, originally, started by cyclists.

To make sure petrolheads don't throw down the book in horror, I've included lots of automotive history. Many automobile pioneers were cyclists before becoming motorists. A surprising number of the first car manufacturers were also cyclists, including Henry Ford. Some carried on cycling right through until the 1940s. For instance, Lionel Martin, who co-founded the Aston Martin marque, favourite of both Clarkson and Bond, James Bond, was a racing tricyclist to his dying day. Literally. He was killed after being hit...by a motorcar.

There will be nugget after revisionist nugget like this and the book, due in August, is already doing rather well. After three-and-a-bit weeks of crowd-funding on Kickstarter the book is triple the original target. Amazingly, it has raised £14,100 in pre-orders, with another 5 days to go. And pledges of cash keep on coming despite the fact the full text for the book will be given away free on the blog-of-the-book.

Why free? There's no point producing a revisionist history and then letting it fester, unseen. By giving it away free I'm hoping a few of the salient facts make it into the mainstream. This mainstream is a motoring mainstream right now. The future could be one where bikes rule the road, just as they did in the 1890s.

How roads were not built for cars | Carlton Reid | Environment | The Guardian

.

.

.

No comments:

Post a Comment