Futures Forum: Planned Obsolescence: and The Men Who Made Us Spend

He also took us on a tour of how we eat stuff which is not necessarily in our own best interests:

BBC Two - The Men Who Made Us Fat

The Men Who Made Us Fat (Episode 1 of 3) on Vimeo

The Men Who Made Us Fat, BBC Two, review - Telegraph

Rewind TV: The Men Who Made Us Fat | Television & radio | The Guardian

The front page of today's Independent brought to light another example of how little we are in control of our food:

New food scandal over peanuts is 'more serious' than the horsemeat crisis

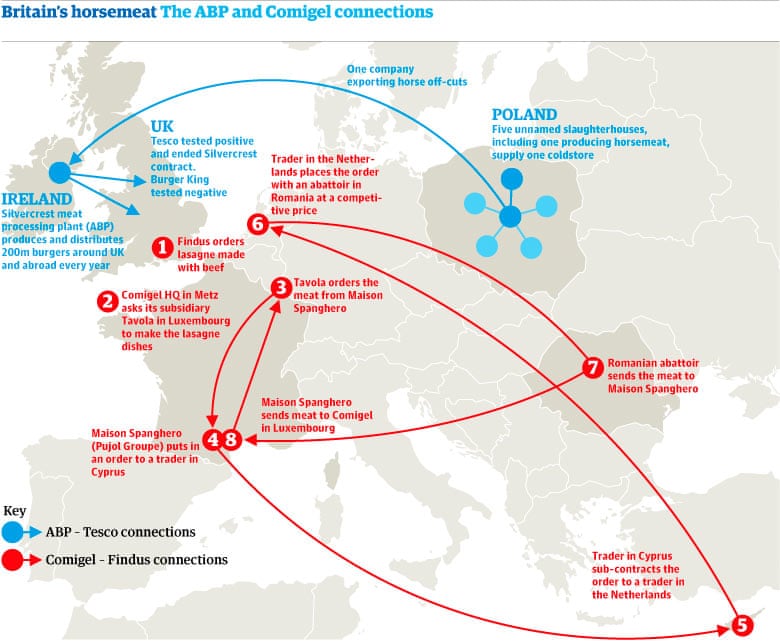

Things tend to get a little lost if the chain becomes too long:

Horsemeat scandal: the essential guide | UK news | The Guardian

A year on from the horsemeat scandal, and things are still unclear:

We still don’t know what we are eating – here’s how to tackle food fraud

As the review into the horsemeat scandal shows, food networks are too prone to abuse. It’s time to follow the moneySunday 7 September 2014

Food fraud is a huge problem in the UK, and much of it is as a result of organised crime. Unfortunately, as the report of the Elliott review on the 2013 horsemeat scandal now points out, there is too little evidence to gauge the full extent of fraudulent practices in the industry.

Food mislabelling is widespread, as is the practice of substituting premium commodity products in whole or in part with cheaper ingredients. Actually, substituting modestly priced ingredients with even cheaper ones is not unknown. We might have guessed that substitution was happening – there must be a reason some foods are so cheap – but it becomes serious when, say, ground peanuts are substituted for ground almonds and appear in restaurant meals. This could prove dangerous, or even fatal, to people with allergies.

At the other end of the scale come foods that are systematically adulterated with chemicals or are even completely counterfeit. As an Observer editorial warned, such organised criminal activity could have catastrophic consequences.

We still don’t know what we are eating – here’s how to tackle food fraud | Lisa Jack | Comment is free | The GuardianAnd meanwhile, it seems that all that plastic we throw away is entering the food chain, as reports this week suggest:

Ocean plastic is likely disappearing into the food chain, new study indicates

A landmark study out today finds huge quantities of plastic are entering the ocean. Since much of it isn’t accounted for, says Andreas Merkl, we should be concerned about where it’s ending up

Filipino volunteers pick rubbish during the 29th International Coastal Cleanup at the shore of the ‘Long island’ in Paranaque city, south of Manila. A new study indicates that the plastic problem might be bigger than we ever thought. Photograph: RITCHIE B. TONGO/EPA

When I tell people that we have a problem with too much plastic in our oceans, many invariably say how shocked they were when they heard about vast swirling islands of trash that accumulate in the oceans’ gyres.

I wish this was the full extent of the problem. It is not.

The drifting garbage patches we hear about in the news – such as the “Great Pacific Garbage Patch” - are the tiny tip of a man-made iceberg, accounting for probably just 5% of all the plastic waste that has been dumped, blown or washed into the sea.

New research published today in the journal Science offers the first real estimate at the quantity of plastic waste entering the ocean. And it doesn’t look good. The findings show that between 5 to 12m tonnes of plastics enter our ocean every year. This is on top of the 100 to 150m tonnes likely already in the ocean.

It’s difficult to appreciate the size of this deluge, so let me put it like this: left unabated, in the next decade our ocean will hold about one kilogram of plastic for every three kilograms of fish. Those of us who are divers, surfers, ocean swimmers and boaters all know this sinking feeling when we encounter yet another trashed beach, reef, or bay.

But it’s not just about the aesthetics. What’s truly worrying me is the missing plastic. We don’t know where all this plastic goes. We know that most of it never deteriorates. Instead it “weathers”, breaking down into ever smaller parts, most invisible to the eye. The often-publicized plastic gyres hold less than 5% than the estimated total. Some is trapped in Arctic ice; more sinks to the sea floor; and a good bit rests on beaches and shorelines. But where is the rest?

We know that plastic in the ocean is eaten by animals; we find it in every species of fish we examine, and it has caused the death of countless seabirds, turtles, and ocean mammals.

We are afraid that a good bit of the missing plastic is actually inside the animals. We don’t yet know what this means for humans, but for me personally, this is very disturbing.

It’s easy to feel overwhelmed. But here’s where I have hope: we can solve this problem. To tackle the curious case of the missing plastic, we need to start on land.

The new Science study identifies where the plastic is coming from: it originates mainly in developing countries, with rapidly growing populations and emerging middle classes, which are consuming more and more plastic.

Ocean plastic is likely disappearing into the food chain, new study indicates | Vital Signs | The GuardianPlastic waste inputs from land into the ocean - Science

New Study Shows Plastic in Oceans Is on the Rise - National Geographic

It is difficult to avoid much of this, but we can do quite a lot.

This piece looked at 'relocalisation' and food chains:

Futures Forum: Relocalisation

The Guardian recently looked at other steps to take:

10 drivers for sustainability in global food production and consumption

At a recent roundtable hosted by the Guardian, experts from industry, research and academia discussed how to make the food system more sustainable. Here are 10 things we learned

1. Waste less food

We’re getting better: avoidable household food waste dropped 21% between 2007 and 2012 in the UK according to the Waste & Resources Action Programme (WRAP). The average UK household still throws away the equivalent of six meals every week, but public concern with food waste has grown to be a useful entry point for talking about sustainability more generally. “It’s a lens to look at other food sustainability issues, and an opportunity to start joining things up,” said Mark Barthel, special adviser at WRAP.

2. Look beyond waste

There’s no silver bullet for achieving a sustainable food system. Diets, health, land use, labour conditions, energy, water, trade rules and farmer livelihoods all play a part. Reducing food waste is an easy win – too easy, perhaps.

“If you’re a company keen to improve your image, food waste can be a tokenistic way of doing that without looking at other sustainability issues,” said Tristram Stuart, founder of Feedback.

3. Meat matters

The resources embedded in meat dwarf other foods. Beef is particularly resource-intensive, with one recent study estimating that it requires 28 times more land to produce than pork or chicken. Compared to plant staples such as potatoes, wheat, and rice, the impact of beef per calorie is even greater, requiring 160 times more land and producing 11 times more greenhouse gases. But global demand for meat is growing, and taxing burgers isn’t a vote winner. Can we change our diets?

4. Reduce post-harvest losses

The FAO estimates that as much as 50% of harvests are lost before reaching the market usually because of poor harvesting techniques and a lack of suitable storage. This contributes to high food prices and means the inputs are wasted too. “Around 95% of donor funding for food security is focused on production, but encouragingly we’re seeing more investment in reducing post-harvest losses now,” said Jim Stephenson, sustainability and climate change manager at PwC.

5. Revisit crop specifications

Crops are lost in developed countries too, not because of a lack of infrastructure but because so much is rejected for cosmetic reasons. WRAP has been working with retailers and farmers to address this and found that some specifications – such as the permitted circumference of a potato – were arbitrarily set decades ago. Re-assessing those specifications, and finding secondary markets for outgraded produce, can make farmers’ livelihoods more sustainable.

6. Strengthen governance

Food retailers are powerful. They can drive global food sustainability, but have also long had a reputation for some unfair practices, such as cancelling orders at the last minute. Last year, the UK appointed Christine Tacon as its first Groceries Code Adjudicator to oversee the Groceries Supply Code of Practice, which was introduced in 2010 to address such practices. Strong governance can support a sustainable food system in lots of other ways too. “It includes planning laws, trade rules, standards, land grabs, as well as the buying practices of supermarkets,” said Vicki Hird, senior campaigner at Friends of the Earth.

7. Shorten supply chains

Food supply chains have become global and complex over the past few decades. Producers at the end of those chains can find themselves subjected to unscrupulous buying practices or poor conditions, in violation of standards set by governments or private sector players higher up the chain. That needs to change, and it already is, with retailers recognising that shorter supply chains with direct engagement are more transparent. “Risk moves back up the chain, but that’s part of doing business properly,” said Tim Smith, group quality director at Tesco.

8. Include restaurants and catering

The UK public sector spends around £2bn on food and catering services a year, and the eating-out market is expected to reach £52bn in value by 2017. Consumers increasingly want sustainability on their nights out, but restaurants need to catch up, according to Mark Linehan, managing director of the Sustainable Restaurants Association. “In our consumer survey last year, food waste and health and nutrition were the top two issues, and that came out of nowhere. But it’s not a sexy thing for waiters to be promoting.”

9. Focus on emerging middle classes

Asia’s middle class has been forecast to triple to 1.7 billion by 2020. In the past three decades, the number of obese people in the developing world has tripledwith twice as many now living in poor countries as in rich ones. Rapidly changing consumption patterns are creating new environmental and health pressures in countries such as China, Brazil and India, and any effort to drive global sustainability in the food system must take these trends into account.

10. Allow cultural change to set in

The change in attitudes to wasting food may be partly to do with a general austerity trend. But can it trigger more widespread efforts to make our food system more sustainable? Some say a cultural shift is happening. “In other areas, such as transport, the connection young people have with their cars is diminishing,” said Trewin Restorick of Hubbub. “The financial crisis has shifted consumers’ psyche, and that’s a massive opportunity for wider sustainability issues. Gradually, you do shift societies.”

10 ways of improving production and consumption of food | Guardian Sustainable Business | The Guardian.

.

.

No comments:

Post a Comment