House prices rocket by £8,000 in a year, says Halifax | Daily Mail Online

UK house prices rise by more than expected in Nov -... | Daily Mail Online

Britain wealth soars to a RECORD £10trillion | Daily Mail Online

We are also obsessed with natural disasters:

Allianz lowers 2017 profit outlook after natural disasters | Daily Mail Online

Insurance claims for Northern California wildfires... | Daily Mail Online

Indonesia cyclone death toll more than doubles to 41 | Daily Mail Online

The Financial Times recently looked at both:

Risky business: when will the threat of natural disaster hit property prices?

Some of the most expensive cities are high-risk, but the economics of housing there still stack up — for now

In September 1938 a storm hit New York that, meteorologically speaking, was nothing to write home about. By landfall, it had been downgraded to a category-three cyclone. That’s neither particularly strong nor rare — six storms of at least that intensity have been recorded in the Atlantic basin so far this year. And yet, the storm, nicknamed the Long Island Express because it bore down on New York harbour at astonishing speed, remains the deadliest storm ever to hit that part of the US. It killed at least 682 and cost, in today’s money, $5.1bn. Were it to land tomorrow, the damage would cost at least 100 times that amount.

“The problem then and the problem now isn’t the wind damage; it’s the storm surge,” says Bill McGuire, Professor Emeritus of Geophysical and Climate Hazards at UCL. “A surge of 12ft would flood much of Lower Manhattan. That’s where some of the world’s most expensive property is; it’s where Wall Street is.”

A category-three storm would probably close the stock exchange, he says — Hurricane Sandy did, and that was downgraded to a category-one storm. The subway system would flood, people wouldn’t be able to get to work; there would be major power losses, he says, because the US grid is ill-equipped to deal with it. “Shutting all that down, even for a relatively short period of time: the costs would run into the hundreds of billions,” he says. “Easily.”

In the real world, the US is still reeling from the impact of three category-four storms that have battered the country this year: Irma, Harvey and Maria — aside from the human toll, the combined financial damage has been estimated as high as half a trillion dollars, says McGuire. Flooding has severely affected trophy home locations such as Key West, the Caribbean and Miami; and wild fires have ravaged wide areas of California’s Napa Valley — AccuWeather estimates the cost of those fires could exceed $85bn. As Mt Agung in Bali was threatening to erupt this week, planes were grounded at Denpasar airport, causing economic disruption.

According to David Alexander, professor of risk and disaster reduction at UCL, the cost of natural disasters is getting worse not only because storms are more frequent or more powerful — though it’s very likely that they are, thanks to climate change and rising sea levels in particular — but because of the increasingly complex domino effects that disasters can trigger. “We are entering the age of the cascading disaster,” he says.

The example he gives is of the Japanese earthquake of 2011. The earthquake itself killed only about 100 people, he says, but it caused a tsunami that killed 18,000. When the wave hit the Fukushima nuclear plant it disabled the emergency generators, which led to the meltdown of three reactors. “At this stage, it’s hard to tell whether the tsunami or the nuclear release was the bigger disaster,” he says. “It certainly wasn’t the earthquake.”

The long-tail of effects on Japan, its energy proficiency, infrastructure, economy, jobs and house prices is still being felt. In October, a court ordered Tokyo Electric Power Company to pay ¥670m to compensate a golf course near the plant for lost revenues. “We’re much better today at measuring the indirect costs of natural disasters,” says Alexander. “If you can’t put your [bank] card into the slot and pull out your money, that’s an effect and someone will be measuring it.”

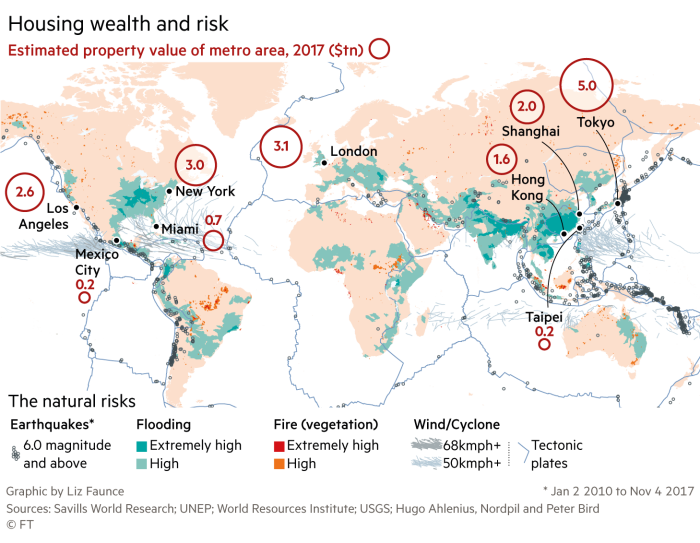

Savills’ new Impacts report details the risks natural disasters can pose to international property markets, and in some cases, the costs can appear profound.

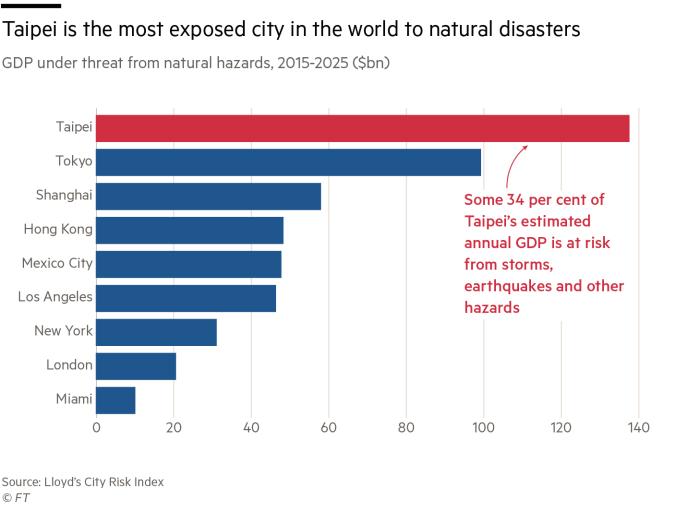

Taipei — which Savills estimates to have a collective housing wealth of about $200bn — is vulnerable to wind storms, earthquakes and flooding. According to Lloyd’s City Risk Index, 34 per cent of Taipei’s projected annual GDP is at risk, making it the world’s most exposed city. “What’s most intriguing,” says Yolande Barnes, head of Savills World Research, “is that the really big cities continue to grow and thrive in risky places, and that’s because their economic advantages outweigh the risks.”

$46.5bn

Amount of Los Angeles’ GDP that is at threat from earthquakes, flooding and drought

In Los Angeles, housing demand has never been greater. The population has grown by 2.2 per cent in the past five years and, over the same period, according to Savills, the price of a square foot of real estate has grown 65 per cent. In September, the median price of a single-family home in the city had risen to a record-breaking $575,000, according to data and analytics company Corelogic. And this is despite the fact that, according to Lloyd’s, Los Angeles is the most exposed city to natural disasters in the US. Aside from its estimated housing wealth of $2.6tn, some $46.5bn of the city’s GDP is at threat from earthquakes, flooding, drought and the rest.

“Los Angeles is subject to — and has suffered — catastrophic earthquakes in relatively recent memory,” says Barnes, “but it’s a huge success story. It brings in people from all over the world [who] are drawn there by the thriving economy and a wide variety of prosperous industries including entertainment, creative and tech.”

In earthquake-prone Tokyo, the property market operates in a different way to most other developed countries and is more closely connected to the risk of natural disasters, says Barnes. Homes in Japan devalue by about 2 per cent a year, and will usually be rebuilt or renovated after 30 years with updated anti-seismic technology.

“So in Tokyo you have an explicit distinction between land value — which is key — and building value,” she says. In the past, earthquake risk has promoted the use of lightweight materials such as wood and paper. “Even without a catastrophic earthquake, there is the expectation that you need to replace buildings after about 35 years because those materials deteriorate — that’s become ingrained in practice.”

The threat of natural disasters — and a tax regime that incentivises people to sell relatives’ homes when they die rather than inherit them — has helped shape people’s attitude to property, says architect Takeshi Hayatsu. “It’s not that people don’t feel an emotional attachment to old houses, they do; but people in Japan like new things. In Japan, new is best.”

The UK is not free from the risk of natural disasters. London is built on a floodplain, but thanks to the Thames Barrier — which limits flooding and storm surge — most of its $3.1tn housing wealth and £600bn annual projected GDP is relatively protected.

The same cannot be said of other parts of the UK. In 2007, severe flooding in parts of Yorkshire, the Midlands and the west of England caused insurers to shell out more than £3bn in claims. “I don’t think the concept of the cascading disaster has really hit the insurance markets yet,” says Alexander. “The insurance markets seem to have simply been thinking in terms of the usual linear relationship: hazard strikes vulnerability equals impact — which is how we’ve thought about these things for 100 years — but the fact is many of the implications of cascading disasters are simply not known.”

In the wake of Harvey, Irma and Maria, reinsurance company Munich Re warned shareholders that payouts from the storms would result in a third-quarter loss and could cause it to miss its profit targets for the year.

The US’s National Flood Program, a government-run insurer, has been in the red since Hurricane Katrina in 2005. It has come under fire as stories about repeated payouts of at-risk properties have come to light. For example, a house on the banks of the San Jacinto river in Texas has flooded 22 times since 1979 — and cost the insurance programme $1.8m over that time, despite it being worth about $700,000.

Property owners have become used to offloading risk to insurers, says Barnes, but that may have to change. “The insurance market we have now is arguably a product of the six decades of growth we’ve seen in capital values — people have come to expect growth from property. But buildings cost money to own and maintain, which that value appreciation had tended to hide.”

As property markets around the world enter a period of low capital growth — home values in London are down 0.6 per cent year-on-year, in New York they’re down 2 per cent — insurers are going to have to confront that hitherto hidden depreciation. Property buyers, she says, will also have to pay more attention as they move from flipping homes to maximising yields.

“I think people have been optimistic about risk,” says Barnes, “but the mentality of property owners in the future could become far more risk-averse than they are today because if you’re looking at an income stream, rather than year-on-year capital growth, you’re going to need to pay more attention to natural and man-made risks.”

The other outcome, of course, is that buyers will move away from major cities and concentrate on riskier, higher-yield markets or abandon property altogether. Last year, the gross rental yield on a London home averaged 3.5 per cent, according to Deutsche Bank. In Manhattan, it was 2.5 per cent, according to StreetEasy — numbers hardly likely to excite.

“I think rather than investors changing behaviour, you’ll get different ones,” says Neal Hudson of Residential Analysts. So speculative buyers, who were prepared to accept low yields because they were seeing high capital growth, will disappear and in will come longer-term money looking for sensible yielding assets. In fact, says Hudson, it may already be happening in London’s high-priced, low-yield new homes market, where developers — unable to find buyers — are cutting prices and offering their stock to corporate landlords.

For some — financially speaking at least — the storm has already hit.

Follow Nathan Brooker on Twitter @ncbrooker

Risky business: when will the threat of natural disaster hit property prices?

.

.

.

No comments:

Post a Comment